- Charity Hudley discusses the tendency for sociolinguists, etc, to “study down,” examining “people in statues lower than their own.” Then, in the next section, funding is discussed, but only briefly and only in regards to funding from the NSF, while private funding is barely mentioned. Do funding sources not contribute to the practice of “studying down”? What must be considered in regards to funding for the research to benefit the community as well as the researcher / funder?

- Charity Hudley briefly discusses Wolfram’s notion of of linguistic gratuity: linguistics ‘giving back’ to the communities that they study. She later quotes Rickford (1997) in saying that the relationship is still unequal. Charity Hudley mentions access to education or equitable funding for the community as ways to partner with communities. In what other ways can linguists give back to the people they study?

- Charity Hudley quotes some of the LSA ethics statement, which states linguists should share their work with the community in a way that is comprehensible, and attempt to prevent misunderstandings of their work. Several times in class we’ve mentioned problems with the dense nature of academic writing and difficulties with jargon. We’ve also discussed the problematic nature of requiring our own students to use academic standards when writing. In what ways can we vary our use of written language in order to connect with differing communities: colleagues, students, and the public?

Ladefoged (1992) Questions

- In what ways can you see the objectives of linguists involved in language documentation conflicting with the priorities of the speakers?

- What do you think might cause a speech community to harbor a distrust of linguists? How can these tensions be alleviated?

- What resources and actions are required on the part of the community in order to engage in a long-term language revitalization/maintenance plan? On the part of the linguist(s)?

Blog Post: 12/2/19

The readings for this week deal with social activism within sociolinguistics. Two major questions are debated: 1) How much of an activist role should sociolinguists take, and 2) What form should sociolinguistic activism take?

Bucholz 2018 supports using sociolinguistics as a tool for social change (Bucholz herself even assigns sociolinguistic activism projects to her undergraduate students), but also argues that “while raising the public profile of a social injustice is a necessary step toward changing it, this act alone cannot bring about change (350).” Consequently, Bucholz 2018 advocates for activism that goes beyond raising public awareness. Bucholz argues that redressing linguistic inequality on its own, even if it were truly possible, cannot end racism (and, by extension, all other relevant societal prejudices) and is therefore insufficient as a goal. We must pursue the development of material support for the vulnerable, rather than simply trying to achieve societal parity of language varieties.

Labov 2018 also believes that sociolinguistics should be used for activism. Labov essentially agrees with Bucholz and others that raising awareness alone is not sufficient to effect change. The main point of Labov 2018 is that, contrary to apparent belief, Labov himself does not advocate raising awareness without taking additional steps. Labov particularly highlights his use of contrastive analysis to improve the material educational circumstances of AAE speakers in US schools.

DeGraff 2018 again supports the use of sociolinguistics as a tool for social activism. His paper is primarily focused on pointing out that sociolinguists have pursued material objectives for quite some time and that, while some students and perhaps some scholars may believe abstractly in raising awareness without explicit material goals, the pursuit of material objectives in sociolinguistics is far from a new idea. DeGraff’s fundamental theoretical disagreement with the papers thus far discussed is his belief that awareness raising and more material approaches complement each other, rather than the latter being a stage that follows the former. DeGraff thus believes in the simultaneous application of awareness raising and materialist methods, but he still believes in material approaches and is therefore only slightly differently positioned from Bucholz and Labov on the basic question of how sociolinguistics should approach activism.

Charity Hudley 2013 argues that “the study of sociolinguistics is critical for increased social justice and social change (1),” with the implication that this criticality obligates sociolinguists to take activist stances. The belief that sociolinguistics should be tightly bound with social activism, it should by now be apparent, is widespread in the field. Charity Hudley believes that sociolinguistics needs to be connected to a direct social justice framework to properly move forward in the world of activism. Charity Hudley traces the development of social activism in sociolinguists through four waves. According to Charity Hudley, “even among the first wave of sociolinguists, there were definitely the underpinnings of direct action at the core (5)” and the role of applied, materialist approaches in sociolinguistics has become more prominent with each successive scholarly wave. Charity Hudley thus agrees with DeGraff and Labov that materialist approaches are not new to Sociolinguistics. Charity Hudley also supports placing a focus on “disseminating relevant information that has already been gathered about language variation (10)” and therein supports DeGraff’s view that awareness raising should complement materialist action. The fundamental wrinkle in the present discussion introduced by Charity Hudley is the notion that the sociolinguist does not have the ability to determine what is socially just without the input of the involved community. Charity Hudley firmly supports social justice action in sociolinguistics but believes that the goals of individual sociolinguistic actions should be determined by affected communities and not linguists.

Ladefoged 1992 takes the notion that the linguist is in no position to determine what is best for the community to a position that is unique among the articles surveyed herein: linguists exist to “lay out the facts concerning a given linguistic situation (Ladefoged 1992: 811)” and not to take direct social action. Ladefoged essentially argues that the linguist is not in a position to decide what is right or wrong for a particular community and therefore, instead of pursuing activism, should serve as a skilled contractor who carries out the wishes of the community, rather than interferes in their affairs.

Dorian 1993 is a direct response to Ladefoged 1992. Dorian 1993 argues that, in following the model of Ladefoged 1992, despite having the objective of avoiding making a social judgment that the linguist should have no power to make, the linguist inevitably makes a social judgement by deciding who to work for. To support anyone’s goals is inherently political, so linguists cannot work with any community without engaging in a social action. Dorian 1993 therefore argues that linguists should engage in activism because it is the only option other than doing nothing. The job of sociolinguist (and of linguistic field worker) is an inherently activist occupation, according to Dorian, and the idea of avoiding activism is therefore idealistic beyond practicability.

A synthesis of the readings discussed above amounts to this: to be a sociolinguist is to be a social activist and social activism requires effecting material change. Directly material methods, then, are valuable. The main open question is, how effective is raising awareness as an approach to social change and how best can it be employed?

Jaworski & Thurlow Discussion Questions

- Although of the discussion of linguistic landscapes focuses on how they highlight what languages are valued in multilingual spaces, semiotic landscapes have significance beyond these factors. One example is the significance of grafitti in transforming spaces into zones of class conflict. What are some other examples of semiotics displaying social meaning beyond language ideology?

- How visible does something have to be to be part of the semiotic landscape? The front page of a newspaper displayed in a newstand is part of the landscape, but what about the rest of the paper, which is only visible if one purchases a copy and reads it?

- To what extent is the social meaning embedded in semiotic landscapes inherently implicit? What role do explicit declarations of social reality have in the landscape?

Sociolinguistics Blog Post 11/23: Linguistic Landscapes Meredith Hilliard

A seminal study by Landry and Bourhis (1997) defines a “linguistic landscape” this way:

“The language of public road signs, advertising billboards, street names, place names, commercial shop signs, and public signs on government buildings combines to form the linguistic landscape of a given territory, region, or urban agglomeration.” (25)

While limiting itself to only a few types of media, this definition captures the essence of a linguistic landscape—the geospatial organization of written text in our surroundings, or, according to Singh (2002), “organized intervention that adds to the functionality of a language” via written media available in a public space. Research focusing around linguistic landscapes generally improves the understanding of how this organization affects and reflects language practice, dominant and subordinate language groups, and the presentation of self or group identity within a speech community. Gorter (2013) gives an overview of the state of the field of “linguistic landscapes,” beginning with a review of past research and theoretical approaches, more current approaches and methodologies, and the future directions of the field.

Gorter cites anthologies such as that of Troyer (2012) to indicate that the field is rapidly growing and that it incorporates an extremely wide range of methodologies. Among the theoretical approaches listed are that of Jackendoff (1983), which relies on a “preference model”; Spolsky (2009), which incorporates linguistic landscapes more broadly into the field of language policy and planning, subcategorizing linguistic landscapes as a form of language practice; Shohamy (2006), which argues that language is used in signage as a tool to establish dominance of space; and Ben-Rafael (1998, 2006), which bases its model on four main sociological principles: signage as a form of presentation of the self, as the result of cost/benefit analysis, as a collective identity marker, and as an indicator of dominant/subordinate language groups.

More currently, research studying linguistic landscapes has incorporated a variety of methodologies both quantitative and qualitative, and is influenced by fields such as political science and geography. The field has been rapidly advanced through digital photograph collection, which has been used to exhaustively document signage in concentrated areas for in-depth analysis of the speech community it is sampled from. This quantitative methodology is frequently combined with qualitative measures such as interview data. A few studies that utilize a combination of these methodologies are Garvin (2010), a study that presented “postmodern walking tour interviews” in Memphis, TN to examine people’s responses to the linguistic landscapes around them in real time, and Mitchell (2010), which relied on a triangulation of discourse analysis from newspaper articles, recordings of languages spoken on the street, and photos of the linguistic landscapes in the studied community. Backhaus (2005) and multiple other researchers examine the historical use of signage in a single area, using a diachronic approach. Gorter adds that these multi-purpose approaches have enormous potential in revealing relationships between language, power, and individual and group identity found on signage throughout the world.

Backhaus (2003) is an example study cited by Gorter (2013) that examines multilingual signage in Tokyo as a reflection of power and solidarity. Backhaus describes Japan as a relatively ethnically homogenous country, with only 2.8% foreign-born residents even in its most urban areas; however, the country has a surprisingly diverse linguistic landscape. The study differentiates between “official” signs (set up governmental organizations, accounting for 25% of the total signs) and “unofficial” signs (other, 75% of the total sample) collected through digital photography from the Yamanote Line in Tokyo, providing a “multilayered” image of the city that incorporates business and shopping districts with parks and residential areas. This photographic data was then analyzed for its linguistic content, finding that about one-fifth of the signs contained non-Japanese linguistic material, mostly English, which is a high-prestige language in Japan. Similar to the models outlined in Gorter (2013), in analyzing its results the study uses a model by Spolsky and Cooper (1991) that identifies three main rules for signage use: write in a language you understand, write in a language the intended audience understands, and write in a language with which you intend to be identified. In keeping with the third rule of this model, Backhaus argues that the lack of translation available on unofficial signs is representative of solidarity with speakers of non-Japanese languages, while official signs tend to present languages more equitably, but with Japanese still clearly presented as the dominant language. In short, language usage on signage in Tokyo is cited as evidence of the spatial establishment of linguistic dominance and solidarity.

Heyd (2014) examines how this same negotiation of power through language takes place online via “folk-linguistic photo blogging as an example of twenty-first-century grassroots prescriptivism.” Heyd argues that these blogs are closely connected to the enregisterment of certain linguistic features as nonstandard or uneducated. According to Heyd, the language policing that takes place via this medium is unique in that its use of visual evidence of so-called nonstandard language use is particularly effective in spreading its message, giving users on the same platforms the ability to spread these rapidly within their own social networks and add metalinguistic commentary. However, Heyd draws an important distinction between “linguistic landscapes” and the “folk-linguistic landscapes” she studies: the former are the landscapes analyzed by linguists, while the latter is comprised of the photobloggers’ own analyses of the linguistic landscapes, which cause the digital enregisterment of the features they focus on. Heyd’s main point is that, through this same cataloguing of language use through digital photography, prescriptivism has taken a more “bottom-up” direction—involved in the same negotiation of dominant and subordinate language groups via more explicit means.

Finally, Jaworski & Thurlow (2010) analyzes the practice itself of using space to create meaning through language, chiefly concerned with the “discursive construction of place and the use of space as a semiotic resource in its own right,” and “the extent to which these mutual processes are in turn shaped by the economic and political reorderings of post-industrial or advanced capitalism, intense patterns of human mobility, the mediatization of social life, and transnational flows of information, ideas and ideologies.” Jaworski & Thurlow challenge the approaches of the above researchers by broadening the scope of their research beyond the geospatial use of language to encompass its interaction with nonverbal communication, architecture, etc. To the authors, linguistic landscapes are better defined as semiotic landscapes, and connecting space to meaning is fundamentally dialectic, involving an act of locating the self within space. The scope of this excerpt is therefore somewhat vast in comparison to the others. Importantly, however, the authors establish the concept of spatialization, or the means by which space becomes organized, experienced, conceptualized, and represented, offering a more in-depth analysis of the meaning-making processes at play in the other “linguistic landscape” authors’ more quantitative work.

One question that stayed with me as I read these articles is that of positionality, something we’ve occasionally touched on throughout the semester but that seems to become increasingly important as we examine fields that rely heavily on qualitative analysis. In the field of “linguistic landscapes,” how closely connected are the positionality of its researchers to the conclusions they draw about the communities studied?

Linguistic Landscapes Blog Post

Linguistic and Semiotic Landscapes in the Context of Chinatown, San Fransico

As I have no real linguistic background, I don’t have a wide variety of experience to pull from to discuss these readings in context, nor do I have the necessary grasp of the material to discuss them purely theoretically. Instead, I’ll be starting off by discussing them in the context of my recent trip to Chinatown while I was in San Francisco for an academic conference. The night after I flew in, I resolved to have dinner in Chinatown before the conference started and ate up all my time. Walking through an unfamiliar city after sundown is a daunting prospect, of course, and I wasn’t sure I would be able to find the right place. I wanted an authentic Chinatown experience, after all, not some restaurant for tourists. I needn’t have worried, of course: every aspect of the landscape made it immediately obvious that I had arrived in the right spot, from the signage to the buildings themselves. For context, here’s the Bank of America where I went for an ATM to get cash for dinner, as seen on street view:

There are a number of elements of the linguistic landscape that can be seen in this picture which tie directly into the readings. To begin with, we see the distinction between government and private signs observed by both Gorter and Backhaus: while much of the bank’s signage is multilingual, the street sign is in English only. This pattern is continued throughout the neighborhood. Street signs and other official signage are in English only, without even an attempt to translate them into Chinese, while storefront signage includes both English and Chinese. As I cannot read Chinese, I cannot determine if these signs are using mutual translation or are complimentary, according to Backhaus’ definitions. Applying Backhaus’ concept of the direction of translation, however, most of these signs seem to have English first and Chinese second. This could be interpreted a power dynamic that prioritizes English fluency, either adopted from or imposed by the larger US community, while the use of Chinese in signage might be stylings of cultural identity rather than purely functional.

This can be further understood through the semiotic relationship between text and space, as outlined by Jaworski and Thurlow. The official bank signage (the red sign with the logo and the promotions in the windows) is written in English only, being standardized signs designed by corporate headquarters. However, they are supplemented with more localized signage that mixes English with Chinese, and even writes out the bank’s English name vertically, in the style of Chinese writing. This is supplemented by the design of the bank itself, with traditionally designed pillars and roof tiling. Elsewhere in the neighborhood, buildings with more modern designs, surrounded by official signage in English, are reclaimed through graffiti, such as this mural which is a clear part of the semiotic landscape despite lacking any words:

This all serves to clearly define the neighborhood without the need for any explicit boarder markers. The Dragon Gate serves as the entryway to Chinatown, claiming the space just as is described in the readings, but this is symbolic, not literal. The neighborhood is not walled off; I entered it without ever walking through the Dragon Gate. Nonetheless, it was quite clear to me when I had entered Chinatown.

Identity Construction through Linguistic Landscapes

Th initial conceptualizations of linguistic landscapes presented by Gorter focus predominately on the choice of language in signage, which demonstrates what languages and dialects are considered to have value in the region. The semiotic perspective suggests that the textual content has significance as well in how it ties to place. Jaworski and Thurlow are largely concerned with how text can lay claim to space, but they focus less on how the content of a linguistic landscape can be part of the identity construction of those who inhabit the space, displaying ideologies about far more than just language. The closest they come to this point is when they reference the use of covert racist grafitti. Linguistic landscapes can be much more explicitly ideological, though, a fact well known to anyone stuck behind this guy in traffic:

The linguistic landscape includes not only the street signs and storefront advertisements, but the campaign signs in the yards and the hats on our heads. This is by no means a new development. The explicit ideological expression in the linguistic landscape isn’t a new development; there was a time not too long ago when “Whites Only” signs were a regular part of the landscape of many cities.

What’s new about today’s linguistic landscape is that it extends online. Heyd discusses how online activity showcases and judges linguistic practices, and activity I’m now continuing here in this blog post. I would argue further that the online world has become part of the linguistic landscape. Traditional websites (web 1.0) are carefully constructed just as a billboard or storefront might be, and even a Facebook page or twitter feed is occupies a similar space in the landscape a public, all access, bulletin board. Although in the current political climate, the more appropriate comparison in physical space might be an racially charged argument unfolding on the walls of a bathroom stall.

Discussion Questions for Herring & Androutsopoulos

- The authors discuss how certain medium characteristics affect interaction management, including the lack of visual cues and one-way vs. two-way transmission. How do synchronous or asynchronous exchanges affect interaction management?

- The authors discuss how social practices in CMC can reflect linguistic variation, identity constructuion, and engagement with public discourse. How can this be reconciled with the adage “Twitter is not real life,” meaning that CMC doesn’t reflect the population at large, because only a subset participates?

- In many forms of CMC, we have no information about the identity of the person behind the screen. What difficulties does this add to interpreting social practices?

Enregistering Internet Language – Lauren Squires Discussion Questions

- Early on in her article, Squires introduces the idea that internet language is defined by and enregistered based on its opposition to “Standard English”. This is pretty comparable to the way we define most dialects and “deviations” of language, that is against a “standard”. In this way, can we ever be free of the idea of a “standard language”?

- By and large, it has often been remarked that our society has changed and experienced a technological shift much more rapidly in the last twenty years than it ever has before. Do you think internet speak reflects this rapid change? That is, are we seeing language trends/uses fall in and out of fad more rapidly than in the past? Squires states that markers typical of internet speak, “u 2” or “brb”, occur less frequently than would be expected, could this be a reason why? Have they simply come and gone at a pace we could not keep up with?

- Since the users of internet language and the receivers/audience of internet language vary so vastly, how well can we generalize and draw conclusions about internet language and its functions and indices? Is it acceptable to group all users of internet language under one umbrella even though the way someone engages with it on a fanpage or website may be different from someone on Facebook or Twitter?

11/18/2019 Sociolinguistics and Computer-Mediated Communication/Discourse (Blog Post)

With the rise of technology and social media comes the increase in Computer-Mediated Communication (CMC) and Computer-Mediated Discourse (CMD). As technologies evolve, so do the languages used to engage in CMC. The research in this week’s readings all point to the similar conclusion that internet language does not fall into the pre-existing categories of what makes a language. Thus, sociolinguists set out to find what exactly makes CMC ‘different’ from traditional, non-computer-based forms of communication, and what CMC can teach us about the current expectations of what constitutes language.

In the first article, “English on the internet and a ‘post‐varieties’ approach to language” by Seargeant and Tagg, they initially establish that “key categories that are used to describe linguistic behaviour … are not scientifically ‘real’ so much as historically determined, and thus their unproblematised use in modern sociolinguistics or applied linguistics can be an impediment to or complicating factor in the development of a nuanced theoretical description of the actuality of people’s everyday language practices” (Seargeant & Tagg, p. 497). They explain that the current thinking of what constitutes language is driven by historical and political motivations, thus preventing a modern approach to understanding how people actually use language as means of communication. By the conclusion of their article, they state “an analysis of the components of its meaning … can yet help illuminate how we understand language use, even in contexts where the actual phenomena appear to be diverging, due to the influence of new technologies and changing forms of social organisation” (p. 512). As societies evolve, so does technology and evidently, the languages used for communication follow. With such constant evolutions, it is only practical that the parameters for categorizing language also be fluid, allowing for better understanding, acceptance, and incorporation of CMC into people’s linguistic repertoires on a more socially accepted level. I think the idea that ‘internet speak’ is lazy or catastrophic to language is inaccurate and does a disservice to those who use it by discouraging change and growth. In this technologically advanced world, people are writing more than ever before because technology offers so many platforms and mediums for ideas to be shared. Internet language, while wildly variant in nature, allows for a level of linguistic experimentation that has never been observed before because of the lack of boundaries and rules, and this experimentation should be embraced as an opportunity to learn more about what is required in an effective mode of communication.

The next article, “Computer-mediated discourse 2.0” by Herring and Androutsopoulos, explores the inherent makings of CMD. The article is broken down into 6 sections, with each section focusing on a different aspect of CMD research to date. The first section lays out the historical context of what constitutes CMD and how it is classified. Section two deals with discourse structure, and the large variation in the ‘properness’ of the grammar used in internet language. Section three, meaning, looks into how users’ intentions are accurately conveyed for optimal perceptions through emphasis or CMC-specific tools. The fourth section interaction management, discusses how CMC has many opportunities for miscommunications but users have found ways to circumvent this by developing methods to accurately interpret messages, despite overlaps or pauses in message timing. Section five, social practice, goes into the relationship between CMC and users’ social lives, namely how the accessibility of modern technology leads to changes in what determines social identity and availability for users. The final section covers multimodal CMD, discussing the growth and incorporation of non-text methods into CMC, and how this growth means continued evolution for CMC as a whole. This CMD ‘handbook’ works to dispel ideas of internet language possibly being one homogenous language and promotes the concept of internet language being a mold, built by the user to fit their exact needs for all their different applications and usages. As with spoken and written language, internet language is also not cookie-cutter and cannot be defined in a single definition. Attempts to do so will lead to frustrations and the hindering of further development.

The last article, “Enregistering internet language” by Squires, attempts to explain that while internet language was derived from existing languages outside of/prior to the emergence of CMC, internet language does not necessarily get governed by the same rules as its ancestors. In fact, research suggests that the rules governing pre-existing languages only rarely occur in internet language, and Squires suggests that this leaves room for researchers to use internet language as a research pool for finding out how aspects of language are determined to have precedence over others. Through careful examination and analysis of internet languages used in various data samples, Squires finds that “this enregisterment process does not completely mirror the processes of enregisterment of regional varieties discussed elsewhere, primarily because the enregisterment of internet language does not proceed from linguistic features that bear a ‘first-order index’ of either a sociodemographic category or pragmatic function” (Squires, 481). Squires also suggests that a lack of research and analysis of internet language has led to misunderstandings about what exactly ‘goes on’ during CMC. There exist many stereotypes about how internet language ‘works’ but it takes avid users and participants of CMC to decipher and accurately use the language.

As a frequent user of online communication, I can agree that internet language is much more complex than its stereotypes. While it may appear lazy and dismissive to some, there are many levels of CMC that are yet to be explored. Any individual user’s use of internet language is deeply tied into their identity and a simple text message can reveal a lot more than what the surface level may appear to be. I believe much work needs to be done before CMC can be fully understood from an outsider’s perspective. From an insider’s point of view, many of the things discussed in the articles seem to be common sense and do not feel as though they should have been mentioned. However, considering current noted gaps in research on CMC, these ‘common sense’ ideas must be explicitly stated at least once in order to establish grounds for further niche research in CMC. While I think some of the researchers’ findings were redundant, I also value their scholarly inputs, as they set to put internet language on the linguistic map as more than just ‘lazy internet talk’. With the prevalence and domination of technology in the modern world, it is important for internet language to be recognized as an adequate means of communication.

Blog Post – Sociolinguistics and computer-mediated communication/discourse

The three papers this week center on the study of “Internet language,” discourse using computers, the question of variation, and the question of mode and technological determinism.

To Squires (2010), internet-specific language is enregistered via processes in “ideologies of language and technology” and is “an outcome of sociocultural and historical context.” Features become observable and substantiate the “parameters of a variety and its speakers (or nonspeakers)” (Squires 2010). This enregisterment is fundamentally different from the processes described by Johnstone on Pittsburghese because they’re not geographically-bounded and the mode is text-based rather than speech. Technological determinism has been critiqued, and through the readings, especially Seargeant and Tagg’s (2011) samples of Thai and English codemeshing, technology certainly affects discourse but users seem to adapt easily with little or no loss in comprehension.

Herring and Androutsopoulus (2015) offer a systematic review of computer-mediated discourse and tease out the discussion of technological determinism to conclude: “What aspects of discourse does [technology] shape, how strongly, in what ways, and under what circumstances?” (Herring and Androutsopoulus 2015). They mention that Discourse 2.0 carries with it many of the antecedents that were found in emails and chat, but with the added Web 2.0 social and collaborative features. We’ve moved from the more general classification of discourse into factors, into a more “fine-grained classification scheme” comprised of medium (various technical attributes like message buffer and format) and situation (group size, purpose, norms). This, together with the discussion of interaction management and synchronicity brought to mind how modern online workspaces like Slack or Discord serve as both synchronous/asynchronous chat as well as archives for past messages. Workspaces can be thriving project spaces for vibrant synchronous discussion or they can be more like message boards or forums.

Adaptation

Clearly found in the readings when given technical “constraints and affordances” (Squires 2010), is the adaptability and playfulness of those in discourse: the glyph for 5 that represents the sound ha. 555 = five five five = ห้า ห้า ห้า = hahaha. To the two users and to Thai speakers that have noticed or adopted it, 555 is an enregistered textual input and likely absolutely normal [would that then mean that it’s now “metadiscursively linked to stereotypic personae” (Squires 2010), an index of the third order?] Moving onward, perhaps we see the use of the omnipresent “lol” serving as a casual end-of-turn marker. Speaking of adaptability, Herring and Androutsopoulus (2015) mention the constraints of gaming and the negatively-impacted coherence of a chat when one tries to write as they’re playing a game. Currently, professional and novice gamers on Twitch have adapted to this by getting proficient at playing their games as well as reading the chat. The gamer reads the text in the chat attached to their video feed and responds by speaking. After some time this becomes seamless and normalized—and just a part of the experience constrained by the technology.

Variation

Also at the heart of these papers is the question of variation as a useful way to conceptualize Internet language. Seargeant and Tagg (2011) in the end come to a re-working of translanguaging and the use of a person’s language repertoire in different situations. They can point to features commonly found in studies of internet language, but they can’t say that this particular use is itself a variation as it’s so particular to a person’s style, whim, “script choice, mode and code” (Seargeant and Tagg 2011). I found this refreshing and their examples compelling—the term variety can be advantageously used in cases of researching “cultural and political identity,” a post-variety approach may be a good place to start for specific discourse data.

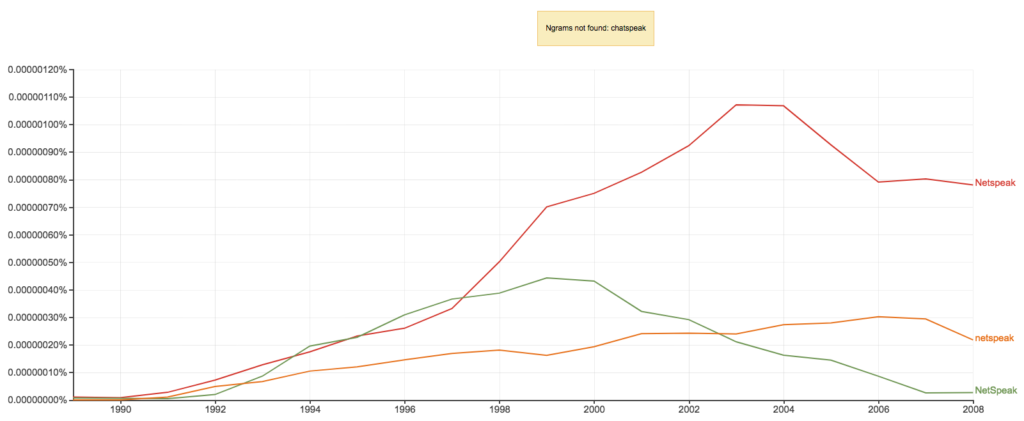

Netspeak and Chatspeak

It’s fascinating to read the early responses to chat speak: “You can learn it the way you would learn any foreign language, with a bit of effort and some memorization skills” (Squires 2010). Although in Squire’s examples and in academic contexts from 2008, I personally haven’t seen the word netspeak for a decade. Google Ngrams uses book scans up to 2008 where all three cases were tapering off or leveling:

At the time of writing, “NetSpeak” (case-insensitive) is found in 2634 articles (314 that are peer-reviewed) in the Graduate Center discovery services (OneSearch). 3 peer-reviewed articles with the term were published this month.

Imperative of Containment

Lastly, Squires (2010) explores the topic of internet language seeping into noninternet contexts and breaching the “imperative of containment”–the stigma on internet language (i.e. non-standard language). This reminds me of an anecdote from the new Gretchen McCulloch book Because Internet:

One linguist parent was delighted by her kid saying “hashtag mom joke,” but another parent was jokingly unimpressed by her own kid’s use of “hashtag”:

My daughter just finished a sentence with ‘hashtag awkward!’ 8 years. It’s been a good run. But the orphanage will suit her much better. (McCulloch 2019)

References

Herring, S. C. and Androutsopoulos, J. (2015). Computer‐Mediated Discourse 2.0. In The Handbook of Discourse Analysis (eds D. Tannen, H. E. Hamilton and D. Schiffrin). doi:10.1002/9781118584194.ch6

McCulloch, Gretchen. (2019). Because internet : Understanding the new rules of language. Prentice Hall Press.

Seargeant, P., & Tagg, C. (2011). English on the internet and a ‘post‐varieties’ approach to language. World Englishes, 30(4), 496-514.

Squires, L. (2010). Enregistering internet language. Language in Society, 39(4), 457-492.