The three papers this week center on the study of “Internet language,” discourse using computers, the question of variation, and the question of mode and technological determinism.

To Squires (2010), internet-specific language is enregistered via processes in “ideologies of language and technology” and is “an outcome of sociocultural and historical context.” Features become observable and substantiate the “parameters of a variety and its speakers (or nonspeakers)” (Squires 2010). This enregisterment is fundamentally different from the processes described by Johnstone on Pittsburghese because they’re not geographically-bounded and the mode is text-based rather than speech. Technological determinism has been critiqued, and through the readings, especially Seargeant and Tagg’s (2011) samples of Thai and English codemeshing, technology certainly affects discourse but users seem to adapt easily with little or no loss in comprehension.

Herring and Androutsopoulus (2015) offer a systematic review of computer-mediated discourse and tease out the discussion of technological determinism to conclude: “What aspects of discourse does [technology] shape, how strongly, in what ways, and under what circumstances?” (Herring and Androutsopoulus 2015). They mention that Discourse 2.0 carries with it many of the antecedents that were found in emails and chat, but with the added Web 2.0 social and collaborative features. We’ve moved from the more general classification of discourse into factors, into a more “fine-grained classification scheme” comprised of medium (various technical attributes like message buffer and format) and situation (group size, purpose, norms). This, together with the discussion of interaction management and synchronicity brought to mind how modern online workspaces like Slack or Discord serve as both synchronous/asynchronous chat as well as archives for past messages. Workspaces can be thriving project spaces for vibrant synchronous discussion or they can be more like message boards or forums.

Adaptation

Clearly found in the readings when given technical “constraints and affordances” (Squires 2010), is the adaptability and playfulness of those in discourse: the glyph for 5 that represents the sound ha. 555 = five five five = ห้า ห้า ห้า = hahaha. To the two users and to Thai speakers that have noticed or adopted it, 555 is an enregistered textual input and likely absolutely normal [would that then mean that it’s now “metadiscursively linked to stereotypic personae” (Squires 2010), an index of the third order?] Moving onward, perhaps we see the use of the omnipresent “lol” serving as a casual end-of-turn marker. Speaking of adaptability, Herring and Androutsopoulus (2015) mention the constraints of gaming and the negatively-impacted coherence of a chat when one tries to write as they’re playing a game. Currently, professional and novice gamers on Twitch have adapted to this by getting proficient at playing their games as well as reading the chat. The gamer reads the text in the chat attached to their video feed and responds by speaking. After some time this becomes seamless and normalized—and just a part of the experience constrained by the technology.

Variation

Also at the heart of these papers is the question of variation as a useful way to conceptualize Internet language. Seargeant and Tagg (2011) in the end come to a re-working of translanguaging and the use of a person’s language repertoire in different situations. They can point to features commonly found in studies of internet language, but they can’t say that this particular use is itself a variation as it’s so particular to a person’s style, whim, “script choice, mode and code” (Seargeant and Tagg 2011). I found this refreshing and their examples compelling—the term variety can be advantageously used in cases of researching “cultural and political identity,” a post-variety approach may be a good place to start for specific discourse data.

Netspeak and Chatspeak

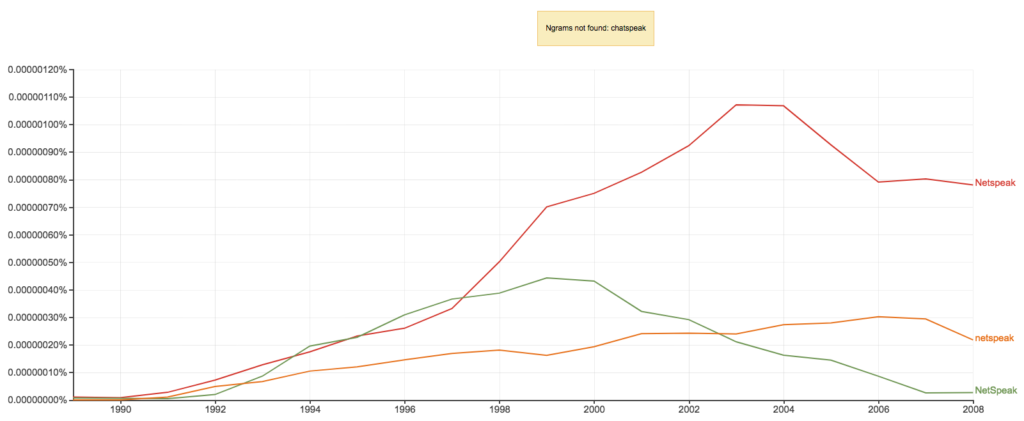

It’s fascinating to read the early responses to chat speak: “You can learn it the way you would learn any foreign language, with a bit of effort and some memorization skills” (Squires 2010). Although in Squire’s examples and in academic contexts from 2008, I personally haven’t seen the word netspeak for a decade. Google Ngrams uses book scans up to 2008 where all three cases were tapering off or leveling:

At the time of writing, “NetSpeak” (case-insensitive) is found in 2634 articles (314 that are peer-reviewed) in the Graduate Center discovery services (OneSearch). 3 peer-reviewed articles with the term were published this month.

Imperative of Containment

Lastly, Squires (2010) explores the topic of internet language seeping into noninternet contexts and breaching the “imperative of containment”–the stigma on internet language (i.e. non-standard language). This reminds me of an anecdote from the new Gretchen McCulloch book Because Internet:

One linguist parent was delighted by her kid saying “hashtag mom joke,” but another parent was jokingly unimpressed by her own kid’s use of “hashtag”:

My daughter just finished a sentence with ‘hashtag awkward!’ 8 years. It’s been a good run. But the orphanage will suit her much better. (McCulloch 2019)

References

Herring, S. C. and Androutsopoulos, J. (2015). Computer‐Mediated Discourse 2.0. In The Handbook of Discourse Analysis (eds D. Tannen, H. E. Hamilton and D. Schiffrin). doi:10.1002/9781118584194.ch6

McCulloch, Gretchen. (2019). Because internet : Understanding the new rules of language. Prentice Hall Press.

Seargeant, P., & Tagg, C. (2011). English on the internet and a ‘post‐varieties’ approach to language. World Englishes, 30(4), 496-514.

Squires, L. (2010). Enregistering internet language. Language in Society, 39(4), 457-492.